Uganda is preparing for general elections in January 2026, marking the seventh since President Yoweri Museveni assumed power in 1986. In advance of these elections, there has been a noticeable increase in repression. What’s different this time is that this repression has spread beyond Uganda’s borders.

On November 16, 2024, opposition politician Kizza Besigye and his assistant Obeid Lutale were kidnapped in Nairobi, Kenya. Four days later, they reappeared in Uganda’s capital Kampala charged in a military court with security offenses. Handed over to Uganda, in blatant disregard of international laws against extraordinary rendition and due process, the two civilians were subjected to military justice.

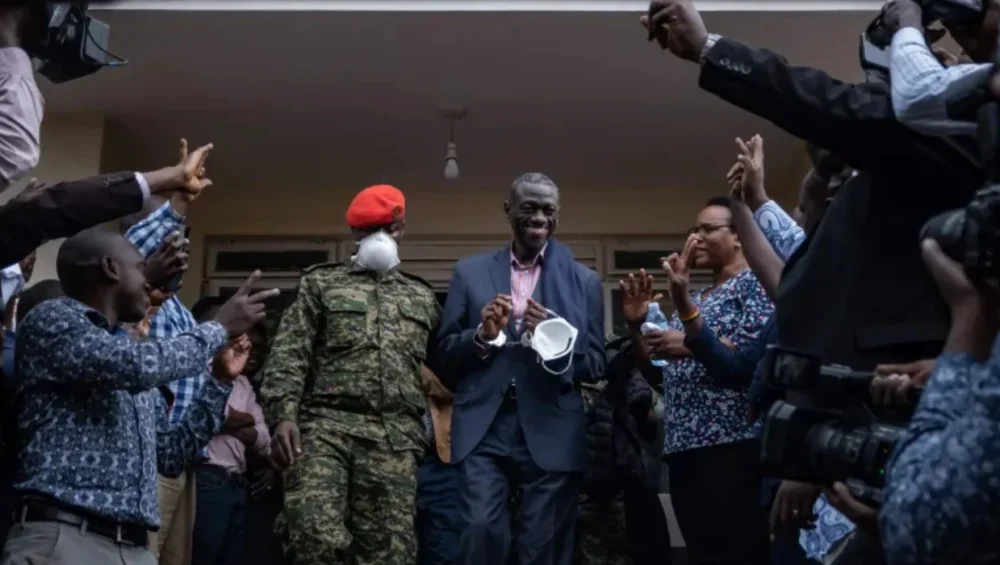

Incensed by this militarisation of justice, Besigye and Lutale won a 40-member defence team headed by Martha Karua, Kenya’s former justice minister. If the state theatrics were meant to muzzle opposition voices, they have succeeded only in doing the opposite. Rather than dissuading others from speaking out, these trials have generated a national debate on human rights and the use of the military.

Uganda’s Defense Forces Chief (CDF), General Muhoozi Kainerugaba, the son of President Museveni, has frequently opined on the case of Besigye on X. Expected to succeed his ailing father, Kainerugaba is the leader of a political pressure association called the Patriotic League of Uganda (PLU), although there is current legislation that bars active military officers from engaging in partisan politics.

Since 2016, Uganda’s Supreme Court had been holding up a decision in a case, initiated by Michael Kabaziguruka, a former MP, claiming trial of civilians in military courts was against fair trial principles. Kabaziguruka, who was charged with treason, claimed that his trial by a military court contravened fair trial guarantees. As a civilian, he averred he was not subject to military justice. The case of Besigye and Lutale provided fresh momentum to it.

On January 31, 2025, the Supreme Court declared that it is unconstitutional to try civilians in military courts and directed that all criminal trials of civilians currently underway or pending must be stopped forthwith and shifted to regular courts.

Notwithstanding this decision, the President Museveni and his son have reiterated their determination to persist with conducting civilian trials with military courts. Besigye protested delays to have his case transferred to an ordinary court through a 10-day hunger strike. The case has since developed into a test case for Uganda’s military justice system in advance of the election in 2026.

Besigye and Lutale are not the only opposition politicians to be tried under military justice. Dozens of supporters of the National Unity Platform (NUP), which is headed by Robert Kyagulanyi, better known as Bobi Wine, have been found guilty by military courts of assorted offences. They include wearing NUP’s signature red berets and other party clothing that authorities said looked like military uniforms, though they were easily distinguishable from military attire. Dozens of lesser-known political activists are also being charged in the military courts.

More than 1,000 civilians have been tried in Uganda’s military courts between 2002 and the present time on charges of murder and robbery among others. To put it into perspective, in 2005, the UPDF Act was amended to establish a legal framework that enabled the military to try civilians in their courts. Coincidence or not, the amendments were being made while the military was prosecuting people arrested between 2001 and 2004, including Kizza Besigye.

Military trials of civilians violate international and regional norms. They create avenues for a whirlwind of human rights abuses, such as coerced confessions, secret proceedings, unjust trials and executions.

Subjecting civilians to military tribunals contravenes Article 7 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights as well as the 2001 Principles and Guidelines on Fair Trial and Legal Assistance in Africa. The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the highest human rights authority in the continent, has publicly denounced their application in Uganda over the years.

Resistance to military justice has not only come from traditional sources. Religious leaders were concerned about the ongoing detention of Besigye after the Supreme Court judgment, so was Anita Among, the speaker of Uganda’s Parliament and a member of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM), who said:

“Injustice to anyone is injustice to everybody. Today it is happening to Dr Besigye, tomorrow it will happen to any one of us”.

In compliance with the court order and general outcry, Besigye and Lutale were remitted to a civilian court on February 21. Besigye suspended his hunger strike. They are still detained, as is their lawyer. Nevertheless, their transfer without a release, initiated by unlawful actions, continues to be problematic. Even after their case was transferred, many more civilians still face pending cases in military courts, with slim chances of being moved to civilian courts.