In August 2025, President Donald Trump intensified criticism of the Smithsonian Institution over its depiction of slavery in museum exhibits, accusing it of focusing too heavily on “how bad slavery was” and failing to present what he referred to as “the brighter side of America’s story.” Through a series of public remarks and official directives, Trump denounced what he described as an unbalanced and “anti-American” portrayal of the nation’s history in the Smithsonian’s presentations.

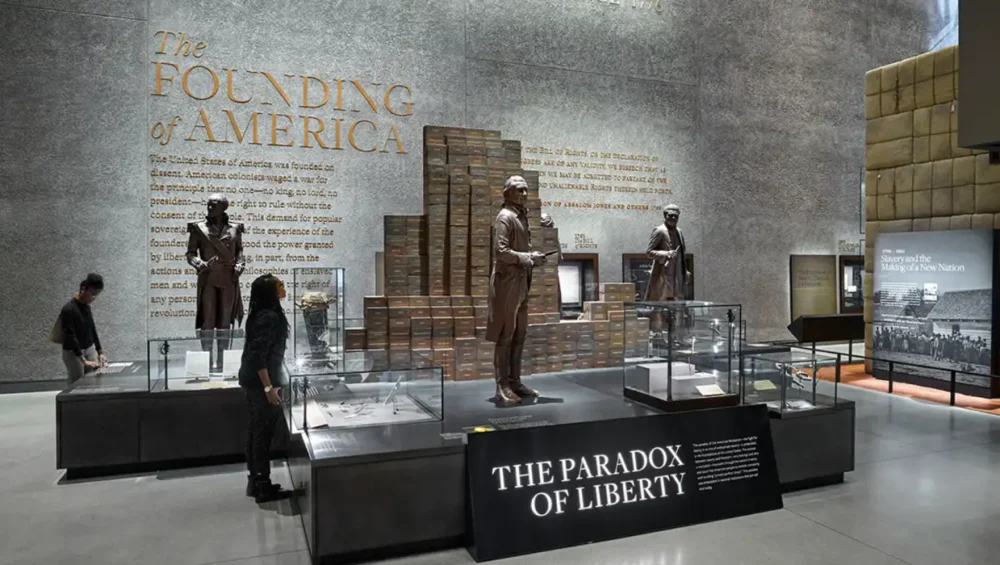

Framing the institution as “out of control,” Trump aligned the criticism with broader administrative efforts to challenge “woke” cultural narratives. His call for reform came alongside a White House-initiated content review across the Smithsonian’s 21 museums and 14 research centers, including the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The administration has argued for a pivot toward “American exceptionalism” in federal cultural institutions and has requested curatorial changes to avoid what it sees as divisive, overly critical narratives.

Curatorial independence under pressure

Under the leadership of its Secretary Lonnie Bunch III, the Smithsonian has always positioned its own way of addressing slavery and race as critical to national awareness. Since the institution has not found a permanent secretary, Bunch, the first Black secretary, has asserted the historical accuracy of existing displays, claiming that addressing uncomfortable facts, including the slavery legacy, is a core requirement of public history.

This has been reflected by curators and scholars throughout the institution who have cautioned against political interference in exhibit content by claiming it threatens the autonomy of scholarship. Smithsonian rules and principles that have been built over many decades stipulate peer-reviewed historical sources and curatorial discussions, which are required to assure academic integrity and accuracy. There is concern that the system of these standards may easily be circumvented by government pressure that endangers the objectivity and educational purpose of the museum system.

Artifacts removed and visitor reactions

It is against this political pressure that reports came out that around thirty artifacts pertaining to slavery and African American history were pulled off the display. One of the most symbolically important ones was a hymn book that was thought to be used by Harriet Tubman in her quests with the Underground Railroad. Other items that were removed were ledgers and enslavement instruments of the plantation.

The removals caused mixed reactions between the museumgoers and the historians, as well. Those interviewed in the Smithsonian in August were alarmed by what they took to be a bid on the part of the museum to whitewash the history of the nation. One of the visitors noted, we must get bigger and we should know our history… we cannot afford to do what we did in the past so badly. Curators reported that artworks were not handled by curatorial agreement, which was not part of the standard institutional practice.

Broader cultural and political implications

The Smithsonian slavery representation scandal has since become a symbol of a larger cultural struggle in the United States as to the narration of history and the privileges of whom to listen to. The issue of national identity, patriotism, and historical accountability is increasingly a battle fought in cultural institutions as the country approaches its 250th anniversary in 2026.

According to some political leaders and critics who have taken the same side of the administration, they believe that the American unity needs a change that is not centered on dominance stories which they reckon contribute to division. They promote shows that highlight novelty, liberty and national success. Critics of this idea claim that it is not a divisive move to calculate the past of slavery in the country but a youthful one, and a requisite towards justice and reconciliation.

Institutional and societal stakes for honoring truth

The more serious alarm that many cultural theorists have cried over is the historical precedence it is lending itself to federal intervention in historical representation. Established institutions such as the Smithsonian have long been governed by a system in which academic curatorial activity remains uninfected with politics. The ongoing conflict is leading to concern that one day that firewall may dissipate.

The autonomy of the Smithsonian has since been challenged by more recent requests on the part of the White House to release internal documents, exhibit planning documents, and staff communications. This amount of federal supervision, according to the agency officials, has never been this high in recent memory and may change the relationship between the national cultural institutions and political leadership.

This individual has said something on the subject and focused on the case of the Smithsonian as a test case that displays more fundamental cultural issues and the problems of politicizing the memory of the past in the open:

Their discussion highlights the paradox of this conflict, which is how the history of the people in this democracy of intense polarization can handle the truth, politics and communal identity.

The evolving balance between history and politics

Although the intervention of the white house has been packaged as a way of restoring sanity and patriotism in federal museums, critics claim the move negates years of effort put in the crafting of inclusive historical narratives. An example is the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which was established partially to challenge the gaps and silence in the mainstream historical narratives. The rewriting of such material or blacklisting of it, says they prevent, can unwind the gains gained in historical knowledge.

Some congressional members have also added their voice to the topic demanding that the issue be heard in congress and that the funding of the Smithsonian be conditional upon adherence to the content requirements. Meanwhile, legal analysts are assessing the challenge of exhibit supervision orders violating the First Amendment values or charter of the institute as a trust tool pursuant to congressional direction but autonomous in its operations.

On the civic front, teachers, historians and civil rights activists have demanded a resurgence in the funding of institutions protecting the integrity of public discourse. The controversy is seen by many as not only a war over the portrayal of slavery, but a harbinger of how America is going to remember its own history as political polarization continues to rise.

With the pressure of public attention and increased congressional inquiry the next moves the Smithsonian takes, either in defiance, accommodation, or re-calibration, will have an impact on the national dialogue at large about who holds the power to narrate history and what facts have to be enshrined in the collective memory. The result will most probably determine not only the future of museum curation, but also the nature of the American collective memory in the decades preceding the semiquincentennial of the country.