Peruvian President Dina Boluarte approved a controversial amnesty law protecting members of the Peruvian armed forces, police and self-defense militias against prosecution on human rights violations during the internal armed conflict between 1980 and 2000. The decade was characterized by a conflict against the Shining Path and Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement as the state underwent an anti-narcotics crackdown, which left over 70,000 dead and thousands disappeared with a disproportionate number of Indigenous and rural natives.

The new law provides amnesty to all those above 80 years who have been prosecuted or convicted of atrocities which relate to state security organs. Its sections reach on at least 600 active investigations that might overrule at least 156 convictions currently made. Whereas the supporters refer to it as closure on aged war veterans, the critics term it as an attack on justice and the rights of victims.

The bill was condemned by rights groups and lawyers right away, since they pointed out that Peru is a signatory to international conventions which do not allow war crimes and crimes against humanity to be pardoned through amnesty. The controversy throws up not only a more basic conflict over how societies can come to terms with painful pasts but also a clash of attitudes to, or even obsessions with, accountability and truth-seeking as opposed to actions that may perilously come at the cost of forgetting.

Boluarte’s justifications and political calculus

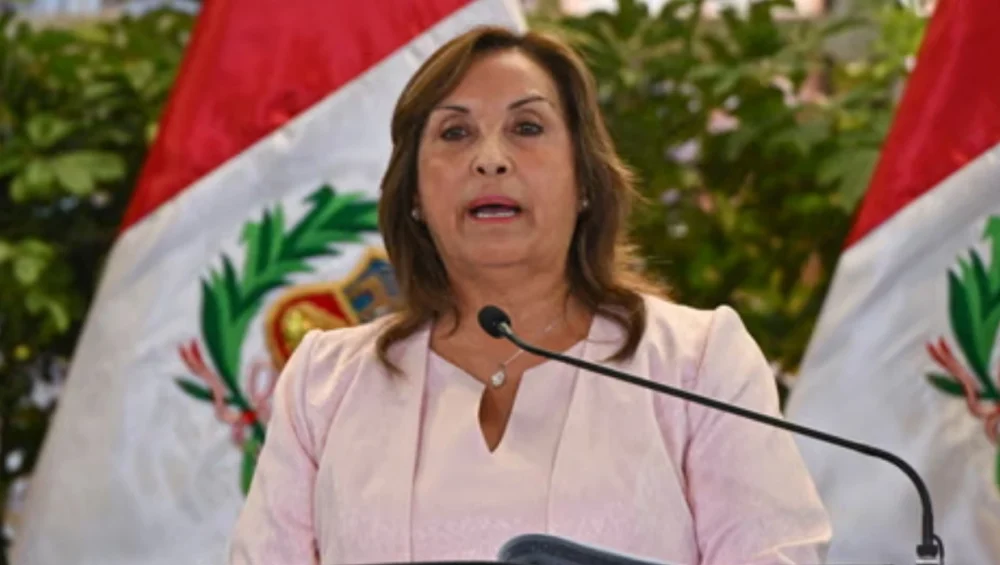

The law was developed as an issue of patriotism, defended by the president Boluarte on behalf of those people who gave their lives in order to save Peru against terrorism. Speaking at the signing ceremony, she called the move a historic day in our country and true to this theme the move was being seen as a national movement to turn the page and foster unity in our country which had been socially divided over decades.

Her rhetoric can be found in line with a more comprehensive political plan that pursues unification of the right-wing associations and security-oriented quarters. Specifically, the Popular Force party, which is headed by Keiko Fujimori, batters military actors who supposedly commit abuses relying on the history of the Alberto Fujimori counterinsurgency. In the case of Boluarte, supporting this law reinforces relations with conservative sectors when the country is faced with increasing political vulnerability.

However, her disobedience of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and its suspension of the law on grounds of breach of international obligations shows clear readiness to fight against supranational institutions at calculated costs. Setti’s denouncement of foreign criticism as meddling in Peru sovereignty is both a vote-catching move by Boluarte based on a claim to nationalistic fervor and made on the expense of increasing legal and diplomatic tensions.

Justice and reconciliation: contradictory paths

To victims and survivors of atrocities committed during the conflict, the effect of the amnesty law is treachery. As UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker T He points out in his comments that reconciliation cannot be achieved at the cost of accountability, especially of crimes committed like extra judicial killings, forced disappearances, torture and sexual violence.

Amnesty International and Human rights watch also protested the law. Human Rights Watch Americas director Juanita Goebertus has cautioned that it destroys years of gains towards accountability and is threatening to entrench impunity in the region. To most survivors, the move by the state to deliver relief to perpetrators rather than justice reaffirms the feeling of exclusion and marginalization, feelings experienced over a long period of time.

The reconciliation challenge

Post-conflict reconciliation is not just some symbolic activity but something that must involve truth telling, justice and acknowledgment of the suffering of victims. The law creates false equivalency, however, through the grant of impunity, by effectively creating a historical narrative that exonerates those in power whilst suppressing testimony of those who were victimized. Instead of uniting, the action will run the risk of further widening divisions by confirming perceptions of the form of justice being denied.

This perception of selective justice raises concerns about whether Peru’s reconciliation process can remain credible. Such measures by the state can only undermine trust and faithfulness instead of making the relationship easier between the communities and the state.

Legal and normative implications for Peru

The conflict between the national domestic law in Peru and the international law of human rights is very clear. Amnesties in relation to serious violations are prohibited by the Convention on the Non-Applicability of Statutory Limitations to War Crimes and by the Geneva Conventions subscribed to by Germany. Inter-American Court of Human Rights has overturned the amnesties enacted in Peruvian in the past twice concluding that they contravene the rights of victims and the state responsibility.

The promulgation of this law has the danger of leaving Peru isolated in international diplomacy, where the country will once again be put on the limelight. The enforceability of supranational judgments comes under question when national governments undermine the international norms in the cause of sovereignty.

The broader implications for justice

The amnesty is posing danger that may sabotage pending trials that have taken long years of arduous activism to raise up. As recent cases, such as the conviction of ten soldiers to systematic rape of Indigenous women in 2024, indicate, efforts can and should be made to hold accountable even though the task is not an easy one. Lawyers caution against the implications of overturned such precedents as it would breach the integrity of the judicial system of Peru and speak to the notion that even crimes against humanity can be pardoned or forgotten over a span of time and political desire.

The voice of experts and advocates

Human Rights Watch researcher Juan Pappier has consistently raised alarms about the devastating consequences of Peru’s amnesty law. In a post on social media, he argued that the measure undermines victims’ rights and erases decades of progress toward accountability, while highlighting its political motivations. His remarks capture a growing concern within the human rights community that Latin America could face a regression in justice standards if such laws gain traction.

Pappier’s analysis situates Peru’s decision within a broader regional pattern of governments seeking to shield security forces from legal scrutiny. For advocates, this trend poses a direct challenge to the principle that crimes against humanity must never be subject to political negotiation or erasure.

Navigating complex realities: sovereignty, justice, and memory

The problem of reconciliation or whitewashing of human rights crimes that afflicts Boluarte shows that there is a great contradiction between conflicting imperatives. On the one hand, her government wants to claim sovereignty, military face and befriend conservative partners. Meanwhile on the other side, the promises made by Peru to the international law and the need of the victims to know the truth and demand justice involving them were still not accomplished.

This tightrope walk highlights a point that frequently recurs in post-conflict societies: can reconciliation and quests of accountability genuinely co-exist and to what extent do the measures of impunity feed the cycles of mistrust and injustice. With continuing international and domestic pressure, the course Peru chooses also promises to influence the reconciliation process of the country as well as debates regionally on the way states come to terms with their past histories of violence.

The implications of this ruling will be felt in Peru and beyond in the years to come as the resolution of the negotiation of memory, sovereignty, and justice in societies with the burden of historical crimes are negotiated.